For the past ten years I have been dreaming, as wakefully as possible, of a sort of return to Eden! Eden the biblical myth is no longer a myth for me. I have always tought of it in a positive, constructive, cold, and realistic way. To my mind, there has never been any question of it being an exotic dream! I have ceaselessly constructed this spiritualized image of this Garden of Eden in an infinite number of probably unknown dimensions. My life has constantly been integrated into this Eden, I moved about in it and existed in it just as truly as I move about in the physical and tangible world.

– Yves Klein, Air Architecture and Air Conditioning of Space

What Paradise and vacation have in common is that you have to pay for both, and the coin is your previous life.

– Iosif Brodskij, Watermark

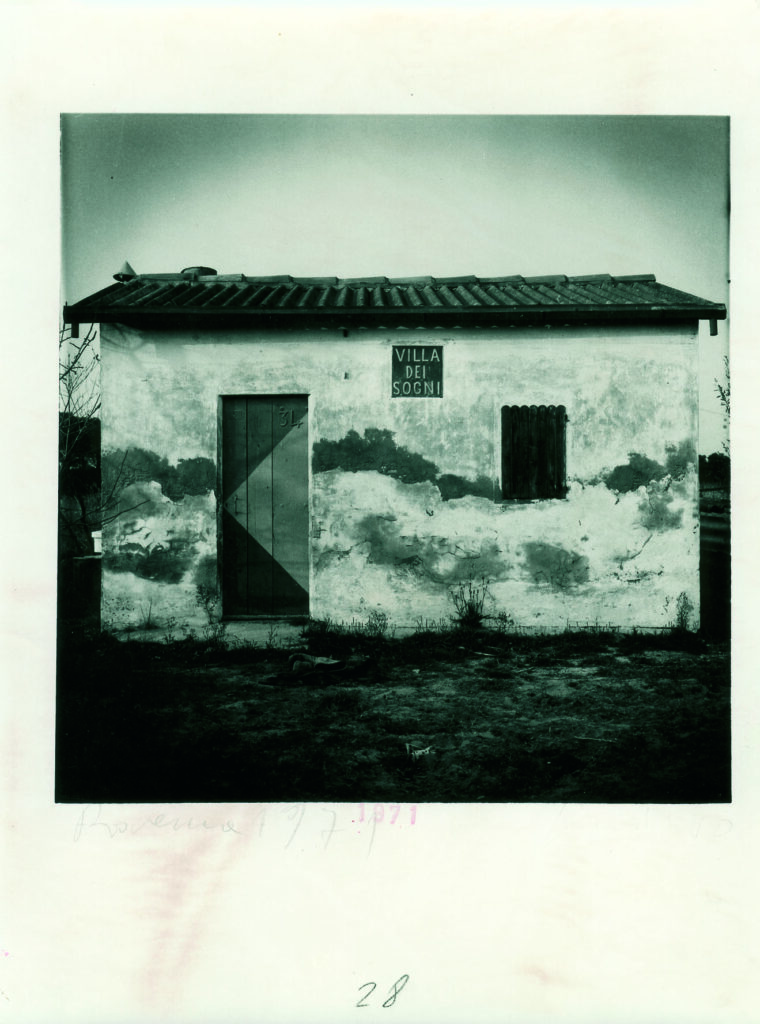

Eden Project aims to give space and visual representation to goals. It seeks to explore the ‘essence’ of pursued destinies, the tangible ‘collapse’ of imagined goals, and the tools employed in the realms of work, life, and thought to achieve them. Karl Kraus once argued: ‘Origin is the goal’. Eden represents the origin, eternally lost and only attainable as a goal. In his theses On the Concept of History, Walter Benjamin referred to ‘progress’ as the project of modernity that compels us to establish Eden as a goal, yet it is our fixation on this goal that perpetually distances us from the origin, leaving us trapped in the melancholic state of lost paradise. In Civita, Giorgio Agamben urges us to contemplate the essence of existence: the possible responses intertwine elusive ideals, entrenched opportunism, fortuitous circumstances, and preconceived notions, all serving as the backdrop for establishing desires and ideals. The goal is an elusive image, encompassing either the primitive and untainted way of life or the perfect city, influenced by the interplay between culture and nature. It can be internalized through the dominance of abstractions or remain unattainable in the face of neo-realisms. The desired destination clarifies the purpose of the journey, sometimes rendering the journey itself as the sole means of bringing it into focus.

Eden, the garden of delights, in its innumerable interpretations and representations, is an enclosed place (indeed the original meaning of ‘paradise’ is ‘enclosed space’). It exists separately from the prevailing logic of the surrounding territory, exclusive in nature, safeguarding its unique contents: a realm brimming with water and diverse forms of life. For Joseph Rykwert, Eden is both a memory and a promise, tangibly evoked by wresting land from urban development, imposing exceptions to the rule – like Central Park in Manhattan; it is often a presence to be rediscovered. Cultural and urban ideals have allowed intellectual, artistic, and architectural endeavours to challenge that promise, giving substance to the extraordinary while averting the perils that accompany it. In his The Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Architects, Painters and Sculptors, from Cimabue to Our Times, Vasari recounts Bramante’s fervent desire to redesign paradise. Despite having achieved his goal, the architect, ridiculed in the text for his megalomania, remains unsatisfied with merely inhabiting it. Instead, he seeks to make it even grander. For Iosif Brodsky, Venice represents the closest approximation of paradise, a city where space contends against the relentless passage of time, aided by the presence of water, an element that mediates its existence. However, as an embodiment of the ideal, Venice is also a highly coveted holiday destination.

In film narration, Eden’s time intertwines past and future: instant of a distant time that becomes an image that phantasmically parallels every present – it is the unforgettable ‘place’ of ‘wild strawberries’, the Rosebud sled, the ‘woman’s face’ emerging from childhood in La Jetée – but also an unexpected future produced by a hopeless past, like the spaceship launched by Claire Denis toward the impossible goal of a black hole providing an inexhaustible energy source, loaded with lifers who have nothing left to lose and yet, or perhaps on account of this, persist with their little garden outside the solar system (High Life, 2018).

In the late 1950s, Yves Klein envisioned air spaces in collaboration with architects. Initially partnering with Werner Ruhnau and later, from 1959, with Claude Parent, Klein conceptualized environments delineated by walls, roofs, and furnishings utilizing compressed air. These spaces allowed inhabitants to establish a direct connection with the sky and climate. His reflections on these ‘ethereal’ spaces sought to dissolve the barriers between nature and architecture, aspiring to return to an Eden, as the author himself defines his goal, specifying its non-exotic but realistic characteristics.

In the new millennium, amidst the proliferation of sprawling megalopolises that seem to be the true goal or culmination of various defining needs, the terms ‘Eden’ and ‘Paradise’ resurface in the names of various projects. In 2001, Nicholas Grimshaw realized The Eden Project in Cornwall: two huge transparent domes that house Mediterranean and tropical biomes. By introducing enclosure into the equation, the project incorporates the third dimension, enabling control of the air and allowing exotic flora and fauna to thrive.

In 2014, through the project Aegean Paradise. Tourist Accommodation in a Garden, amid.cero9 explored an alternative spatial model for hosting mass tourism on the Greek island of Symi. It envisioned an island within the island, serving as a communal house, an extensive public space, and a landscape. Amid.cero9 states: ‘In this strange induced Third Nature, filled with the intoxicated air of new and expected forms of beauty and pleasure, a series of artificial, bizarre and excessive pieces are intended for the other part of life, the contra-routine, a hallucinatory and temporary compensation for the everyday life, the grey and unsatisfactory reality’. An isotropic and simultaneously fragmented system is envisioned within a bubble of earth, encompassed by a slender roof originating from a column – oscillating between nature and project – conceived by the French Renaissance architect Philibert de l’Orme. Paradise City is a recently built new tourist hub in Seoul, less than a kilometre from the international airport of the metropolis. It comprises six buildings including hotels and tourist attractions. Nightclub and Wonderbox, two buildings facing each other, designed by MVRDV, are characterized by their windowless structures, their distinct forms instead offering glimpses of golden accents and radiant entrances: paradise here lies absolutely within.

Every holiday implies seeking refuge from a familiar, perhaps comfortable, and necessary place in favour of atolls surrounded by crystal clear waters, lush exotic flora, and lunar stillness. The tourist village was conceived precisely to encapsulate and regulate this great alternative to urban life, allowing for moments of respite and unconventional, refreshing ways of living, to immerse oneself within a confined space while enjoying an expansive horizon. In the context of seeking an escape, the island (much like an oasis) remains the tangible embodiment of Eden: difficult to reach, ostensibly unspoiled, yet habitable.

While The Line, a linear city being constructed in Saudi Arabia, promises an extensive, exclusive Eden carved out from the desert, the Terrorism Confinement Center is simultaneously taking form in San Vicente as the largest prison in Latin America. These two contrasting city concepts, one linear and the other dictated by ‘rational dispositions’, re- emerge from distant pasts and dystopian interpretations, and present themselves as attainable goals. The prison structure, designed to accommodate 40,000 inmates in a manner reminiscent of Dante’s Inferno, reveals the other side of Eden. Both projects invest in an apparent infinite development, shaping or negating perspectives regarding the surrounding territory, and giving space to the drowned or the saved.

According to neorealism, altering the status quo is difficult, with only the potential to scratch the surface, offer commentary, or introduce contamination. But perhaps the desired goal is already within reach; all that is needed is the ability to see it. Perhaps we need to heed the transformative potential of The Milk of Dreams (evoked at the Venice Art Biennale in 2022), which manifests its influence in tangible ways, or focus on radical visions such as those depicted in Liam Young’s epic video The Great Endeavor, where an army of mega-structures and a multitude of workers engage in a great environmental counter-offensive to rejuvenate the air. Alternatively, we can also turn to resources like the delirious solitude depicted in Guido Morselli’s Dissipatio H.G., that imagines the resurgence of environmental architecture, where the golden city and the vacant yet intact black houses in the valley come into focus; or zoom in on details, as in Marina Ballo Charmet’s work dedicated to anonymous street corners, in minute and monumental detail, to find different perspectives.

Vesper is structured in sections; below the call for abstracts and the call for papers according to categories. All final contributions will be submitted to a double-blind peer review process, except for the section Tale. Following the tradition of Italian paper journals, Vesper revives it by hosting a wide spectrum of narratives, welcoming different writings and styles, privileging the visual intelligence of design, of graphic expression, of images and contaminations between different languages. For these reasons, the selection process will consider the iconographic and textual apparatuses of equal importance.

Vesper is a six-monthly, double-blind peer-reviewed journal, multidisciplinary and bilingual (Italian and English), included into the list of scientific journals compiled by the Italian National Agency for the Evaluation of Universities and Research Institutes (Italian academic areas 08 – Civil Engineering and Architecture and 11 – History, Philosophy, Pedagogy and Psychology, with the exception of their bibliometric subfields). Vesper is indexed in SCOPUS, EBSCO, Torrossa and JSTOR.

Timeline

Sections: Project, Essay, Journey, Archive, Ring, Tutorial, Translation, Fundamentals

Abstracts must be submitted by September 1, 2023

Abstracts acceptance notification by September 15, 2023

Papers submission by November 5, 2023

Sections: Tale

Papers submission by September 1, 2023

Papers acceptance notification by September 15, 2023

Publication of Vesper No. 10, May 2024

More information can be found in the full call for papers here.